photo courtesy of New York Botanical Garden, C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium

These - and more - can be found in

"Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World's Plants" by Barbara M. Thiers

.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

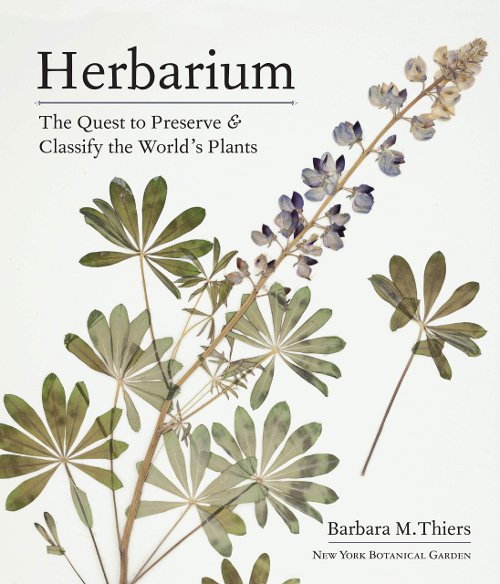

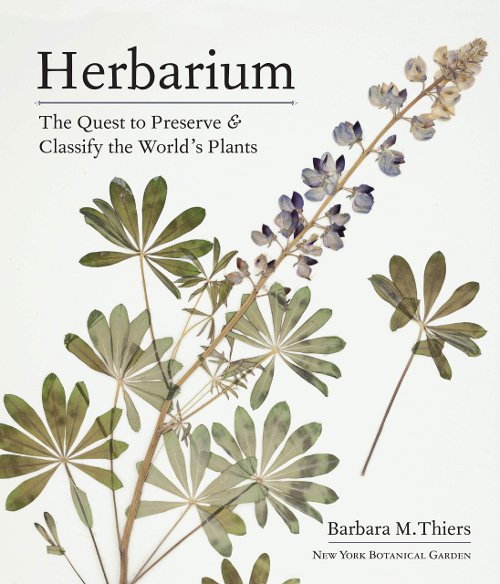

Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World's Plants, a book review

Friday, 29 January 2021

Herbarium. What comes to mind when I say the word. Perhaps tall cabinets, away from the view of the general public, filled with sheets upon sheets of flattened, dried plants. That's true, but only part of a very important story, where people went to places close to home and off in the wild, collecting and preparing specimens to be brought back for careful study. Don't yawn and think to yourself, "Who cares?" Gardeners should care. Herbarium contain records of garden plants and others found in the wild. They hold the "type" record of first discoveries. There are fascinating stories of plants found, lost, re-discovered.

photo courtesy of New York Botanical Garden, C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium

These - and more - can be found in

"Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World's Plants" by Barbara M. Thiers

I know a little about herbarium, having made occasional and infrequent use of the New York Botanical Garden's William and Lynda Steere Herbarium when doing research for one or another of my books. There are standards for pressing specimens, mounting them, label information, the sheets on which they are arranged. But these parameters did not spring into uniform existence. They developed over time. So, where to begin . . .

For Barbara Thiers, it began in her childhood. Her father was founder and curator of the herbarium at San Francisco State University. Her childhood weekends involved assisting him with various details and activities. Fast forward to 1981. Starting a one-year post-doctoral fellowship at the Steere Herbarium, Thiers abruptly discovered the difference between a contemporary research teaching herbarium and one of the world's largest and most active. And Thiers never left, once that year's fellowship concluded.

So where and how did herbaria originate?

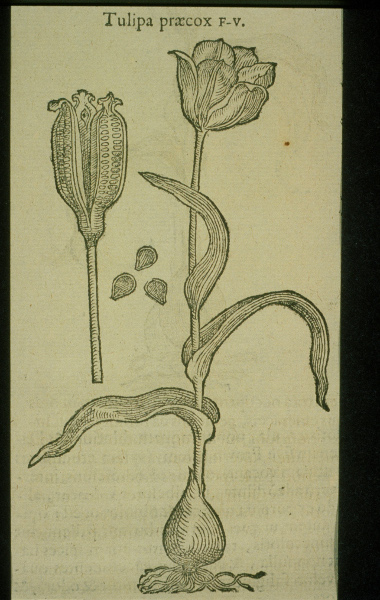

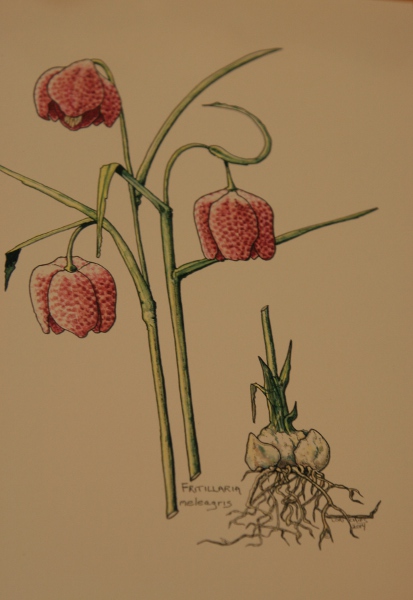

Herbals were once illustrated with woodcuts, such as

this tulip from a 16th century work of Carolus Clusius.

illustration courtesy of the artist, Lori Chips

Botanical art offers more and finer details, and color.

as this lovely Fritillaria meleagris by my friend, Lori Chips.

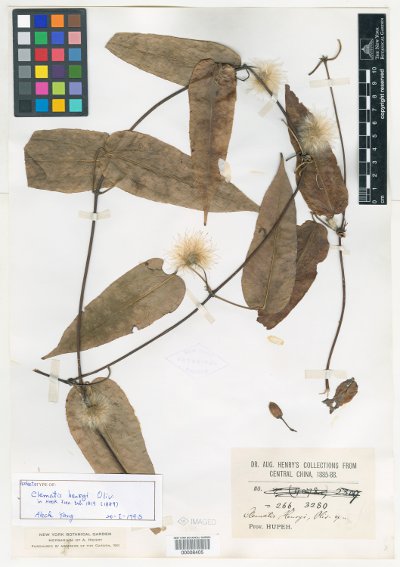

Image courtesy of the C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden

Note: The color target is a standardized color reference used to capture

optimally exposed and accurately color balanced images under any illumination.

However neither the woodcut nor the botanical art have the same reality as an actual herbarium specimen of once living plants. Here is the type specimen, the one that is the foundation against which any Clematis henryi specimen must be compared for confirmation.

Description of an earlier herbarium bound as a book - with thickened margins to allow for the specimens that, even pressed, have some modicum of height. Fascinating to think of plant specimens from the 16th and 17th century, to look at an illustration which show a pressed tomato plant that includes the fruit (from which the pulp was removed for better flattening, I suppose.) Excellent descriptions of what category of plants were first studied (vascular ferns, conifers, flowering plants), later expanded to include algae, mosses, liverworts, hornworts. And then fungi. This is a lovely, easy to follow book from which to learn more about plants.

Herbarium moves afield from the Eurocentric study of plants that is, perhaps, what most of us are familiar with, to the Indian subcontinent where samhitas, ancient Sanskrit texts documented medical practice, mention of Islamic discussion of plants in the Qur'an, Aztec, and more. "But of all the world cultures with a long history of plant documentation, Europeans were the only ones to preserve specimens as part of the process."

Then, in the 18th and 19th century voyages of exploration criss-crossed the world. It was trade that drove these journeys. The botanists and collectors were tag-alongs, though the commerce of the spice trade was indeed renumerative. Thorough descriptions and photographs of how specimens are prepared offer a glimpse into life in the field. (Take notes, in case you find a four-leaf clover.) Think what it was like when sailing ships were the mode d'emploi for journeys from the United Kingdom to Australia where everything was strange and unknown to the Europeans.

Of course, while plants "know" who they are (it is written in their genes) people are determined to name them. It was Linnaeus who developed the system of binomial nomenclature that we continue to use today, and this is lucidly explained. This is not a stodgy book stuffed with only images of elderly plant specimens faded to brown. Oh, they are there. But there are maps and paintings, drawing, buildings, wonderful stories of people passionate about plants. Names you might recognize: Captain James Cook, Joseph Banks, Paul Gauguin.

The book's next section moves closer to home with the development of herbaria in the United States. John Bartram had a garden in Philadelphia. He collected plants from New England to Florida, travelling by horseback, sending seeds and specimens to England. It was he who discovered

Franklinia alatamaha, never seen again in the wild after 1830.

Lewis and Clark's expedition westward, two years crossing the continent from their starting point in St. Louis and yes, collecting plants. Some specimens were subsequently lost, temporarily or (so far) permanently, some that were found had been damaged by beetles. The remaining 222 specimens have been digitized and are stored in a climate-controlled room specifically designed to hold them. And of those specimens 76 are type specimens, a foundation for our knowledge of flora west of the Mississippi River in the interior of North America. Story after story, each more fascinating than the last, such as the California earthquake and the damage it caused to the California Academy of Science on Market Street in San Francisco. And of course an perusal of Nathaniel Britton, his wife Elizabeth, their founding and development of The New York Botanical Garden.

Modern times. The digitization of herbarium labels. Specimens are stored by their Latin names. But what if you wanted to find plants of California. Or even more specifically, plants collected by Willis Linn Jepson, in California. Yes, that Jepson who wrote the Manual of the Flora of California. Well, now you can.

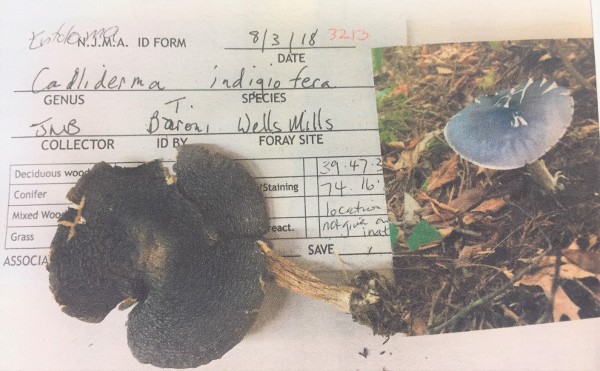

There are fascinating stories about the people collecting the specimens stored in herbaria here and abroad. For example, not all specimens in a herbarium are flowers, grasses, trees, and shrubs. The New York Botanical Garden's Herbarium has a Cryptogamic Herbarium in which there is a specimen of an interesting little mushroom

indigoferus.jpg)

image courtesy Dorothy Smullen

that was collected by Job Bicknell Ellis in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, back in 1879.

Thiers describes him and his fungal exsiccatae, dried fungal specimens in numbered sets.

In 1896, near the end of his life, Ellis sold his collection of over 80,000 specimens

to the New York Botanical Garden for its Cryptogamic Herbarium.

And there it sat, never seen again in the wild for 137 years.

Now we depart from the New York Botanical Garden's herbarium to the Ray Fatto - Gene Varney Herbarium of the New Jersey Mycological Association, housed at the Rutgers' Chrysler herbarium. The New Jersey Mycological Association organizes forays. In August 2018 - well, you can read what happened in this snippet from their newsletter:

image courtesy Dorothy Smullen

.

image courtesy Dorothy Smullen

And this is where the inestimable value of a herbarium and its specimens becomes obvious.

Let me tell you another story, as we finish our look at this wonderful book.

Early in 1839 Asa Gray traveled to Europe examining herbarium specimens of American flora that had been collected by European botanists. He spent some time at the herbarium, Jardin des Plantes, in Paris. While there he saw a specimen collected somewhere in the Carolinas by André Michaux in 1788. Describing it as an unknown plant, perhaps a species of pyrola, Michaux flattened, dried, prepared the specimen (leaves, no flowers), and eventually it ended up in the Paris herbarium. Upon seeing it, Asa Gray felt it was not a merely new species, but a new genus. He and his friends spent 39 years looking for living plants in the Carolina mountains.

In 1858 Asa Gray studied a collection of Maximowicz's Japanese plants and recognized in his Schizocodon uniflorus another species of Shortia almost identical with the Carolina plant. How to explain disjunct distribution - the occurrence of closely related species in scattered locations separated by substantial barriers to migration such as oceans. Plants growing in Japan closely related to plants found in eastern North America, but nowhere in between. He coined the term vicariance to describe the occurrence of two closely related species at widely separated locations, so that each species is the geographic equivalent of the other. And this would not have been possible without the herbarium specimens collected by botanists separated by time and space.

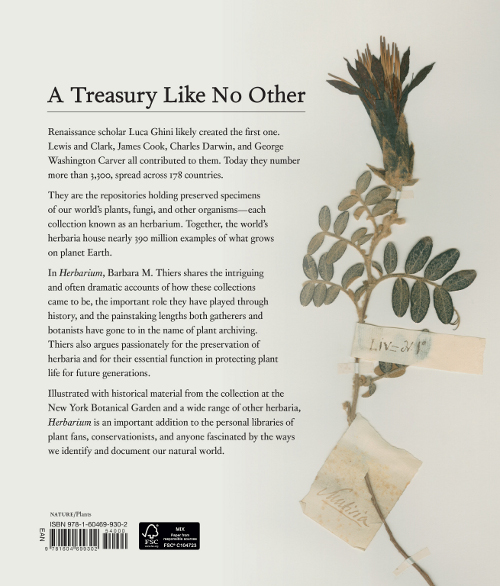

photo courtesy of Royal Botanic Garden, Madrid, Herbarium

Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve & Classify the World's Plants

by Barbara M. Thiers

published by Timber Press

Hardcover, ISBN: 978-1-60469-930-2

published 2020, $40.00

A review copy of this book was provided by the publisher.

Back to Top

Back to January

Back to the main Diary Page